Perón's dangerous letters in exile: instigation of armed violence and efforts to smuggle weapons

Throughout 1956, the political construction of Juan Domingo Perón was revenge.

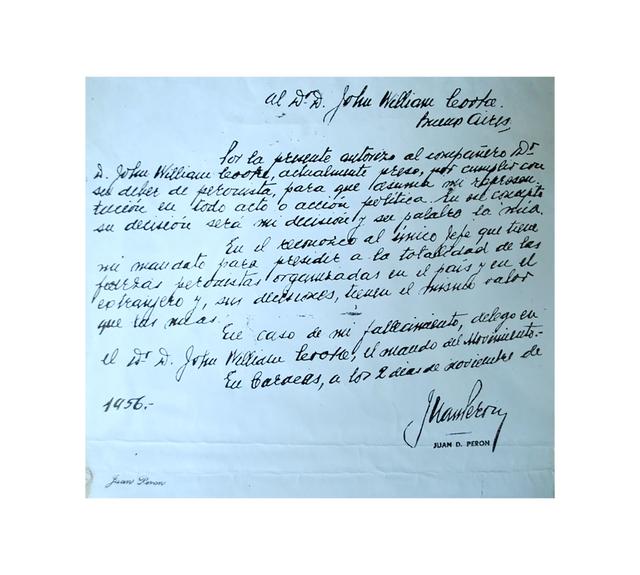

Their objective was to grow the hatred of the people against the military government and promote chaos until it was overthrown. Although his epistolary recipients were multiple —he wrote thousands of letters during his exile—, he had placed his faith in John William Cooke, the youngest, bravest and also rebellious deputy he had in Congress, and at the same time who he designated as his heir in case of death and put in charge of the popular insurrection plan in Argentina.

On June 12, 1956, he wrote to her:

“The hatred and desire for revenge that exists today in millions of Argentines will one day become a 'driving force' and that force, harnessed through good organization, will yield extraordinary results . Desperation, hatred, revenge, often arouse forces even greater than enthusiasm and the ideal. People who do not react out of enthusiasm only react out of desperation: this is what is being achieved in our country. Executions will only speed up the process.”

Perón had not encouraged the civil-military rebellion of general Juan José Valle in June 1956, and it had not been carried out in his name either:

“We will not follow the military who promise us revolutions every weekend. They see the popular state and want to take advantage of it for their purposes or to serve their inclinations as 'saviors of the Fatherland' that a military man always carries with him. But here it is about the fate of a people and not about the concerns or ambitions of any man.

It was evident that Perón did not want exile to make him lose his role as leader.

“Five months ago I gave the instructions: through the forces of the people, chaos could be achieved. Ours was a social revolution and this type of revolution had always started from chaos and, consequently, we should not fear chaos but provoke it and use it for the benefit of the people. The economic chaos and the emerging misery and deprivation will cause many others to join the resistance. All this work remains for us to do, helped by the incapacity, ignorance and violence of our enemies We must organize the comprehensive struggle by all means”.

Later, Perón pointed out to Cooke the path of resistance:

“The people have to wage guerrilla warfare, which in resistance is characterized by the sum of all actions. The sum of small acts of violence committed when nobody sees us and nobody can repress us represents as a whole a great violence by the sum of its parts. We must organize ourselves conscientiously in hiding. Instruct and prepare our people for the purposes that we propose, group ourselves in disciplined and well-framed organizations by capable, bold and determined leaders, who are respected and obeyed by the masses, carefully plan the action and adequately prepare the execution through permanent exercises. If this requires the use of the Devil, we will use the Devil in due time. The Devil is always prepared for this.” (See Perón-Cooke. Correspondence, volume I, Buenos Aires, Granica, 1973, pages 113 and 17).

In 1956, just under a year after his overthrow, every power base he had capitalized on in nearly a decade was being razed. The military government outlawed the Peronist Party and intervened in the Evita Foundation, the CGT, the trade unions, and replaced the National Congress with an "advisory board." Thousands of leaders and activists were arrested and persecuted. The jails were filled with political prisoners. A decree prohibited mentioning Perón and his late wife in public. Neither could the bass drum be used in the Carnival murgas, as it was considered a “Peronist instrument”.

To achieve a dramatic effect, the Liberating Revolution showed Evita's jewelry and party dresses as evidence of the embezzlement of public coffers. The statues and busts of the spiritual head of the Movement were removed from public places, her photos were burned, and her embalmed corpse was also stolen and hidden.

On the other hand, some of the former officials began to form political parties under the banner of “Peronism without Perón”, to form the “soft layer” of Peronism that sought “pacification.” In addition, Perón had lost much of his prestige among many trade unionists who previously revered him.

In the epilogue of ten years of government, Argentine society had been divided between those who idolized him and those who hated him.

Meanwhile, Perón clung to the typewriter to boost the morale of his followers. On July 11, 1956, he wrote to Cooke:

“Hatred and the desire for revenge have already exceeded all tolerable limits even in ourselves in the face of so much infamy and criminal spirit. It is necessary to confess that even if we were saints we would have to dismember the traitors and murderers of innocent citizens and defenseless prisoners. I left Buenos Aires without any hatred but now, faced with the memory of our dead and murdered in prisons, tortured with the most atrocious sadism, I have an inextinguishable hatred that I cannot hide”.

But the key piece of that entire stage were the General Instructions, which he sent to the Peronists of the resistance and the exile commandos so that they could disseminate and apply them. he Recounted how to carry out crimes against his enemies and how to prepare the “guerrilla war” for the final assault.

The Instructions exhibited such a manifest degree of violence that many believed they were apocryphal, but he himself took care to confirm their veracity. There he explained:

“The enemy must be attacked by an invisible enemy that hits him everywhere, and he can't find it anywhere. A 'gorilla' will be left as dead by a shot to the head, as crushed 'by chance' by a truck that ran away. The property and homes of the murderers must be subjected to all kinds of destruction by means of fire, bombs, or direct attacks. This fight must be relentless, remembering that in every 'gorilla' we kill there is salvation of many innocent citizens who, if not, will be killed by them. The gorillas must come to the conclusion that the People have sentenced them to death for their crimes and that sooner or later they will die at the hands of the People. The means to eliminate them matters little, we have said that the vipers they are killed in any way”.

Perón also proposed organizing “diabolical” sects, under the name of Justicia del Pueblo, to combat the Aramburu government:

“The relatives and friends of the dead, the persecuted and imprisoned, the dispossessed, etc. they have the right and moral obligation to be part of these sects dedicated to punishing the guilty. Your organization will be permanent and will not be dissolved for any reason before fully fulfilling its mission. Those who enter them must think carefully before because they cannot desert later. The following will be formed: a) In each city, town, establishment, etc., the necessary number of Territorial Sects . b) In each trade union body, the corresponding Trade Sects. c) In each constituency, department, etc., the corresponding Political Sects. Each of these 'Sects' must have a list of the enemies of the People, with their corresponding addresses and personal information, headed by Aramburu and Rojas, as well as their direct and indirect collaborators and the hitmen of the Armed forces. According to these lists, the murderers and traitors of the People will be convicted and punished. It doesn't have to be immediate, you can wait until the occasion arises. They must know that one day or another they will be sanctioned. The brothers who join the sects will receive a number to designate themselves and a code word to recognize each other so that each one has, instead of a name, a number, and instead of a last name, a code word. Admission will be made in a ceremony presided over by the leading brothers and, the entrant will swear there "eternal hatred of the enemies of the people", will receive a small recognition credential and will be read the obligations they contract with the institution. All meetings are secret and the brothers, while in them, will cover their faces with a hood that prevents them from being known. The treatment between them is secret and they will only be individualized by means of their number and the code word. There is only one penalty for traitors: Death. Agents who infiltrate through deceit must be drastically suppressed as soon as they are discovered. The leading brothers, appointed by the sect itself, must know the background of each candidate for membership. It is the obligation of all associates, of all sects, to investigate everything related to the disappearance of the corpse of the Martyr of Labor —Doña Eva Perón— and it is the duty of all associates to establish the direct and indirect culprits to kill them. Not a single one of those vipers should be left alive.”

Perón wanted to hit violently and in any way to make the country ungovernable, but the power of his message did not arrive in the best conditions. Most of the letters he received were controlled by the FBI, and the ones he sent were stolen, lost, or arrived at the wrong time. Invented manuscripts also circulated, which hindered his instructions.

In addition, Cooke, the head of the Peronist Resistance, had been arrested in November 1955, and transferred to different prisons, and the capacity of the Federal Capital Command that he had created, despite his efforts, it was very limited, as its members had no experience in clandestine actions. They were frequently arrested.

After all, the actions of resistance against the military government —burning means of transportation, industrial sabotage or “pipes” against public departments— were spontaneous, had great operational difficulties and were outside the control of the Peronist Superior Command that Perón was driving from Caracas.

In Venezuela, Perón received exiles, local officials and anyone who came from Argentina. He outlined the lines of action to follow, talked about the world situation and listened to business proposals. For each visitor he had a word of approval and encouragement.

On one occasion he received a trade unionist; they talked politics for a while and then he wrote her a letter of support. The visitor returned to Buenos Aires believing himself to be his delegate. Within a week, exactly the same thing happened with another trade unionist: conversation, letter of support and wink of representation.

One of his collaborators asked him the reason for that attitude.

“My son,” Perón said, “I have to encourage them all equally and unite them behind a common mission, but I also have to make them face each other. If not, I'll never know which one is better.

Perón explained his ambiguity as a feature of political leadership, an efficient formula to stimulate the internal life of the Movement. When the conflicts between his subordinates got out of hand, he played down their importance, citing internal quarrels or figurative problems. At one point, he claimed that someone was abusing a representation that he did not have.

For Cooke, his boss's ability to encourage diverse groups represented a headache: no one was fully subservient without a direct order from the General.

Appointed head of the Operations Division of the Higher Command, Cooke was encouraged, by means of a letter, to update Perón on the practical inconveniences that this modality generated.

It was specifically due to the case of Jorge Daniel Paladino, who worked in the Peronist Resistance with an important management of men and weapons in urban guerrilla actions, and had plans to set up a machine gun factory .

Around 1957, Paladino traveled to Venezuela and received Perón's “blessing”. He brought letters and pasta discs with the General's voice that allowed us to infer that he was his representative. With the impulse of Caracas, Paladino began to tour Buenos Aires and rebelled against Cooke's authority.

Cooke then wrote to Perón:

“News began to arrive from everywhere saying that Paladino declared that he was his direct representative before the Commands and Worker Groups, and shared with me on an equal footing the management functions, etc. As I was carrying his records and letters, the confusion was great, because while we are laboriously reaching the unit that we so badly need, on the other hand those activities make people think that you are playing some kind of game that consists of which on the one hand orders me to unify, and on the other encourages anarchy. [...] I suggest that I be expressly authorized to let Paladino know that he must abide by the specific functions of the mission entrusted to him and that he refrain from playing the caudillo”.

Perón acknowledged Cooke having given Paladino a credential, which he could use only to recruit people to use in sabotage missions. And he promised that if Paladino “continues interfering with him, we will publicly disavow him. He's a good guy who's done a lot of acting already, but he's definitely gotten all fuss over his head”. With that written endorsement, Cooke retained the letters and pasta discs that Paladino had obtained. (See Perón-Cooke. Correspondence, op. cit ., volume II, pages 29-30 and 40) .

Perón continued with his policy of intransigence towards the Aramburu government, with permanent calls for chaos and sabotage until the objective conditions were reached to cause his fall. Also, during this stage of his exile, he searched for businesses that would allow him to buy weapons. He knew that a revolution could not be sustained with pocket handouts in gatherings of locro and empanadas, among exiles. However, the money he made was never enough to sustain a state of permanent insurrection.

This lack became an obsession.

In one of his letters to Cooke, Perón curses the time that activities such as writing, guiding, indoctrinating and, above all, leading a tangle of organizations take away from him —commandos abroad; clandestine groups; union, military, ideological or insurrectionary fronts; links—, which, in addition to their precarious capacity for action, disperse their efforts in innumerable internal intrigues.

“I can assure you that, if I have the necessary time and peace of mind, in a short time we will have enough money to provide abundantly for the needs that arise. I am doing some business that will allow us not to wait any longer. We must buy the weapons and send all the elements across the borders, maintain relations in the country where we are, where we can get a lot of help, but we must connect and work, and finally the need to have I have a certain peace of mind to be able to think about things”.

To save that scarce time and avoid constantly intervening in disputes and frictions, he delegated communication with the commandos to Cooke. I explain:

“If you, from there, lead everything related to the resistance, organization and preparation of the forces and prepare from now on the actions that allow you to be in a position to act when the occasion arises, I will be able to send you the weapons and explosives necessary, as well as the essential economic means to help the Exile Commands and the interior of the country with the necessary funds.”

In the same vein, Perón was active in the “black market”:

“A short time ago we lost a consignment of weapons that I was offered because we didn't have the necessary money to pay for them, but I hope to be able to get a similar one in the future. In Brazil we have contracted so that the weapons are delivered in Argentine territory and they run everything related to smuggling. Naturally, they charge more, but we have more chances of obtaining money than here, in the necessary amount.” (See Perón-Cooke. Correspondence, op. cit., volume I, pp. 185-186, and p. 324 ).

Some time after these letters, during his stay in Ciudad Trujillo —now Santo Domingo, capital of the Dominican Republic—, and with Arturo Frondizi as president, Perón got rid of John William Cooke.

The former deputy had been functional to his strategy of revolutionary war for more than two years, responsible for the arming of the "hard line" of Peronism with activists of the Peronist Resistance. But after signing the pact with Frondizi, Perón began to erode his internal leadership and put him on an equal footing with those who had sought to accommodate first with the Liberating Revolution and then with the “integrationist” policy of the Civic Union Intransigent Radical (UCRI), seduced by the official heat.

Cooke's influence within the Movement was reduced with the creation of the Peronist Coordinating and Supervisory Council, a new representative body, Perón's “tactical arm”, which included multiple leaders, most of them belonging to the “line soft”.

They all watched each other and reported directly to the General.

With this strategy, Perón achieved a double effect: on the one hand, he undermined Cooke's internal power; on the other, by integrating the “soft layer” into the leadership of the Movement, he avoided the diaspora, although, according to his letters, Perón trusted in his own power of annihilation :

“I do not believe in the fable of 'integration' and even less in the 'swallowing' of Peronism by the UCRI, as some fear. If Frondizi were to "buy" some Peronist leaders or some Peronist leaders wanted to "relieve" or "cabrestiar" on Frondizi's side, a single word would be enough to annihilate all those who volunteered for such an unworthy act. Peronism, due to its mystique, its doctrine and the politicization of the masses, is in a position to expel half of its leaders without losing a single vote. We do not have caudillos”, he wrote.

In January 1959, the workers' strike that resisted the privatization of the Lisandro de la Torre refrigerator was enough for the new Peronist Council to collide with Cooke's revolutionary line. Qualified as “crazy and terrorist”, they accused him of promoting an alliance between Peronist and communist workers in the conflict, which was repressed by Frondizi, as an exercise prior to the implementation of the Conintes Plan: < b>hundreds of trade union leaders were imprisoned.

Cooke imagined that Perón would come out to support him. He wrote that he felt aggrieved by the organization, and informed him that the Justicialista Party, which had been legalized in some provinces, was becoming contaminated with "corrupt" who negotiated for money the end of a strike or its integration with Frondizi. Under the facade of “unity” and devotion to the Leader, Cooke warned him, the worst scams were being committed.

After receiving that letter, and for a long time, Perón stopped writing to him and appointed Alberto Manuel Campos to replace him. Cooke, persecuted by the Frondizi government, went into hiding, was marginalized from the Movement, he decided to take refuge in Cuba, where he was captivated by the speeches of Fidel Castro and the clamor of the crowds.

On the island he remembered with nostalgia, but also with an aspiration for the future, Perón on the balcony of the Casa Rosada. Cooke tried to convince the Cubans of the revolutionary character of Peronism and resumed correspondence with the General from Havana, in his desire to project him as a leader of Latin American liberation and differentiate him from the rest of the dictators who were refugees from Trujillo.

But in his letters to the General, Cooke did not fail to write down his warnings: Peronism —he affirmed— should define an ideology, which for Cooke was to fight for the liberation of the proletariat through war of guerrillas. For most of the Peronist leaders, on the other hand, ideology was defined by loyalty to the General.

For several years, Cooke appealed to Perón's revolutionary fervor and invited him to reside in Havana. He had the support of Fidel Castro. But the General remained immune to his entreaties, and it took Cooke a long time to understand how fruitless it was to continue this increasingly one-sided correspondence.

(The epistolary exchange between Perón and Cooke was published for the first time at the beginning of the 1970s. It had a lot of influence on the young people who joined Peronism from the left, because they showed Perón as a promoter of revolutionary ideas , especially in volume I).

Marcelo Larraquy is a journalist and historian (UBA). The last book of his published by him is “We were Soldiers. Secret history of the Montonera Counteroffensive”. Ed South American, 2021.

CONTINUE READING:

From the state of siege to the helicopter, a chronology of the last 24 hours of De la Rúa in power“Now everything rots”: when Rucci foretold the tragedy of Peronism over Cámpora's candidacy for president“The finger on the trigger”: how was the duel between Perón and Lanusse that ended with the return of Peronism to power

1613