Stolen memory: the hidden stories of the cultural looting of Latin America

David Hidalgo

¡Atención! Este artículo tiene más de un año y puede contener datos desactualizados | |

| 16 octubre, 2016 12:23 pm | | Tiempo de lectura: 17 minutos |

Atención! Este artículo tiene más de un año y puede contener datos desactualizados |

| 16 octubre, 2016 12:23 pm |

| | Tiempo de lectura: 17 minutos |

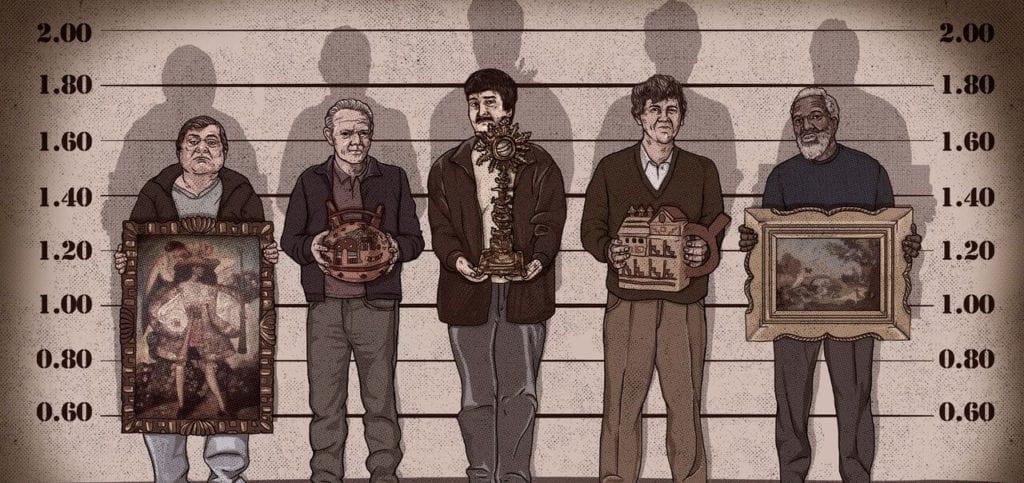

Cultural heritage traffic is an activity that connects from antiquarian and politicians in Buenos Aires to Narcos in Guatemala, and from collectors under suspicion in Mexico to diplomats in Costa Rica and Peru.This special was made among five journalistic teams of the continent and reveals the scheme of the international art market that allows the sale of stolen objects of temples, public museums and private collections.It is the first journalistic research of cultural traffic with massive data and includes a database that constitutes the beginning of the first Latin American census of stolen cultural goods.

In September 2010, the Lempertz auction house, the oldest in Belgium and one of the most prestigious in Europe, announced the sale of a lot that fired the alerts of seven Latin American embassies accredited in Brussels.The catalog was full of pre -Columbian pieces that Peru, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Bolivia recognized as part of their cultural heritage.The efforts against Interpol and the Local Police exhausted, the agents of those countries requested an emergency meeting with the Belgian Foreign Ministry.They were waiting for a tense meeting, as had happened months before another auction, but the minister who received them had an encouraging news: Belgium had just ratified the UNESCO Convention of 1970 that seeks to control the import, export and traffic ofcultural goods in the world, and was determined to comply with it.The only problem was that each country had to present previously documented evidence that the pieces belonged to him, which had also been stolen, and, above all, that there was a judicial case that claimed them.Everything, when just three days were missing for sale.

After the meeting, intense coordination between the embassies and their foreign ministries began to achieve those evidence."Without them, it is impossible for the Belgian Government to do something to stop this auction," reported Guatemala Business Manager from Brussels, according to documents in the case that for the first time come to light as part of the Stolen Memory Project, an effortJournalistic that has understood the review of judicial files, alerts of robberies, technical reports, secret reports and interviews in six countries, to unveil the transnational mechanisms of cultural heritage traffic in Latin America.

The documents were obtained and analyzed, at the initiative of Eyopublica, by an alliance of journalistic teams composed of the nation (Costa Rica), Public Square (Guatemala), Political Animal (Mexico) and Checking (Argentina).

One of those reports indicates that the same day of the meeting of Latin American diplomats in the Belgian Foreign Ministry, a spokesman for the auction house communicated to explain his position."He assured us that the Lempertz house is respectful of the law, and that before each auction they make sure that the pieces to be sold are not stolen," said the Central American diplomat.Lempertz's spokesman said that his procedures included sending the police a list of objects that were going to auction, and that the owners were asked to sign a sworn statement about their legal origin.The format of the document - required for this investigation - has barely half page with three questions based on the word of the declarant.It does not require more documentary evidence than an attached list about objects to be consigned for sale.

Despite the efforts, none of the embassies could demonstrate in time the illicit origin of the pieces.The Belgian Foreign Ministry declared without competence to intervene in the case.The auction was held anyway on September 11, 2010.

It was at least the second effort of several Latin American countries to stop the sale of cultural heritage goods in the region in the same year, as can be seen from the reports examined.Eight months before, the embassies of Peru, Mexico, Ecuador and Bolivia had claimed for another auction of the same Casa Lempertz, which announced pre -Columbian pieces from "a private European museum".In the lot there were pieces of the cultures Chavín, Tlatilco, Tumaco and Tiahuanaco, among others."Several of the objects contained in the catalog of the auction belong to the Red List of Latin American Cultural Property in danger of the International Museum Council (ICOM)," warned the letter sent by the four embassies together to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Belgium.The effort would fail for the same cause.

Both incidents reveal the ravines of the global market for looted goods in Latin America.Only between 2008 and 2016, the main auction houses in Europe and the United States put more than 7 thousand objects of the archaeological heritage of Peru for sale.In a similar period, between 2010 and 2016, the authorities of Costa Rica detected the sale of relics of their past in at least thirty -three auctions, and those of Guatemala on 26 occasions, according to official reports obtained for this investigation in eachcountry.The volume of Latin American pieces sold to collectors from the main capitals of the world is even greater than the 4,907 cultural objects that Interpol now seeks as stolen throughout South America, Central America and Mexico.

It is what would be called a missing museum.

This panorama - reconstructed with documents, databases and direct sources - throws lights on episodes that occurred throughout the American continent, and also highlights the route that links countries with the greatest cultural heritage of the continent and the centers of the antiquarian marketInternational, as a scale of the traffic of stolen goods towards some of the most important academic institutions and research centers.

Traffic routes

At the beginning of July 2014, the Interpol de Lima office sent Message No. 6608 to the organization's subsidiary in San José, Costa Rica.I had the ‘urgent’ character.The Lima agents reported that "there would be a possible network of traffic of Peruvian cultural goods that would have come out illegally from our territory to their country, and then be transferred to the United States of America".The alert came from information obtained by the Ministry of Culture of Peru and gave precise details about the stolen pieces, the characters involved and their whereabouts: the message asked to intervene to two Peruvian-American citizens called Juan and Ingrid Bocanegra, owners of a place inThe La Paco Shopping Center, in the exclusive San Rafael de Escazú, an area of luxury hotels, condominiums and corporate buildings of the Costa Rican capital.It was presumed that there were a group of valuable works of art sought from Lima.

The lot consisted of about forty paintings among which there were nine copies of the Cusco School, the most famous colonial art current in the Andes, with frames carved in mahogany and cedar and veneered in golden bread.The group also included "many more rolled oils," added the report.The paintings could not have come out regularly, since they would have required a ‘export certificate of goods not belonging to cultural heritage’, issued by the Ministry of Culture of Peru.In the previous seven years, the Ministry had barely granted 11 certificates of that nature to Costa Rica.None coincided with the pieces under suspicion.According to the intelligence analysis, the cargo was going to be sent to three directions in Washington, Miami and Indianapolis.One of those paintings was a portrait of the Virgen de las Mercedes, the patron saint of inmates.

According to the migratory records of San José, Juan and Ingrid Bocanegra - 79 and 73 years, respectively - Costa Rica have visited indistinctly about ten times in the last two years.They usually identify with both their Peruvian passports and the Americans.The last time that Juan Bocanegra admission to the country was on June 29.He left for almost a month later.

The Costa Rican Route of Global Cultural Heritage Traffic was confirmed with another episode that same year, when Washington's customs authorities intervened a suspicious package that had been sent by express mail from San José.It was a cardboard tube that supposedly contained a document valued in just a dollar.When the police reviewed the content, he found that it was actually a painting with the image of an harlequin painted in Gouache technique on paper.Had the signature of Pablo Picasso.In the same tube there was an authenticity document that also confirmed its true value: more than 70 thousand dollars.

Then reserved coordinations were made between the police authorities of both countries to catch the trafficker who had sent the package.When Costa Rica's police raided the condominium indicated as the direction of the sender, he only found a retired ex -worker from the Judiciary.They had falsified their identity.Picasso's painting is still confiscated in Washington's customs.No one has appeared to claim it.

"The borders of Central America are very permeable," says Monserrat Martell, specialist at the UNESCO Culture Program in San José.“In customs and airports there is a lot of corruption.As much as we form the staff, if there is endemic corruption, the pieces will never be detected, ”he says.

Costa Rica is one of the Latin American countries that has reported less cultural goods stolen from Interpol: just twenty.They are mostly paintings from different eras, which are paradoxically not protected by the local heritage law.This standard only considers the protection of pre -Columbian objects.Just two pieces of such are sought with an international requirement of Costa Rica: a stone metate and a ceramic vessel in the province of Guanacaste, one of the most important centers of Central American pre -Hispanic cultures.This, despite the fact that in recent years the San José authorities detected about 214 pre -Columbian objects that were going to be auctioned in houses in Europe and the United States.The National Museum of Costa Rica was not successful in claiming them because it could not demonstrate its origin with documents.

The paradox of the case is that the character who is considered one of the greatest traffickers of pre -Hispanic heritage in the history of Latin America is a man born in Costa Rica.His name is Leonardo Patterson and lives refugee in Germany.At the time, it was claimed by the authorities of Peru, Guatemala and Mexico for the illegal sale of hundreds of archaeological pieces, from ceramic objects to golden pieces of incalculable value.If he was never convicted of this crime, it was not for lack of evidence, as a report that is part of this investigation is demonstrated.Patterson is the proof that in Latin America it is easier to catch a narco than an alleged art trafficker.

Eyopopublic / Gastric Juice / Rocío Urtecho

Criminal ties

At the end of November 2015, a police operation to capture a drug trafficker alerted the authorities of Guatemala the new ties of art theft with other circles of organized crime.The Prosecutor's Office had ordered the capture of a subject named Raúl Arturo Contreras Chávez, 43, on which he hung an extradition request from the United States.Contreras, a type of robust contexture and hard expression, was investigated by the Department of Treasury as a member of a network that sent cocaine to the EE.UU since 2004.According to the Miami Prosecutor's Office - Revised for the Stolen Memory Project - the organization was made up of fifteen people, among which there were also four Lebanese and several Colombians.The day they caught him, Contreras was in a semi -west residence in Guatemala City.He had no drug, but he kept several works of art hidden in various furniture.

That day the police counted 24 pieces, including 12 paintings of the colonial era and 10 religious statuettes.Some images looked the original gold bread they had at the time of theft.The Expert Team of the Department of Prevention and Control of Illicit Traffic of Cultural Assets - a three -employed office at the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture - determined that 11 of those works came from an assault occurred six months before in the Foundation for Fine Arts(Funba), in the former Guatemala, for an armed band that seized hundreds of silver objects and old paintings.The other two pieces that appeared with the capture of the narco were reported as stolen from a Museum in Honduras.The Prosecutor's Office did not establish if Contreras had participated in the organization of these assaults.Nor is it known what happened to the other 289 pieces that are still lost.

A possible link is in the case of the six paintings of "The Passion of Christ" torn from one temple by another armed group one year before the robbery in the funba.During the investigation, both the Prosecutor's Office and the Ministry of Culture of Guatemala obtained the version that the theft had been commissioned by a drug trafficker of a lot of power.An informant even came to give the clue that the works had followed the reverse path to Honduras.However, at some point the informant disappeared and with him a possibility of recovering those pieces, which are among the 333 goods that Interpol seeks in the world as part of the cultural heritage stolen in Guatemala.

Central America's authorities have ideas found about the connection between drug trafficking and cultural heritage traffic."Since drugs do not know what the real value of these pieces is, they pay what they are asked," says Eduardo Hernández, of the Ministry of Culture of Guatemala.Prosecutor Rolando Rodenas does not believe that art serves to wash drug money.On the contrary, in Costa Rica it is considered that cultural heritage is a alibi for other illicit businesses."They buy art and antiques because it helps them wash their money and legalize it by acquiring desired parts, which, already clean, can then place in the international market," explains Monserrat Martell, UNESCO specialist in San José.

I was asking my mom about This traditional liniment oil that’s used in the philippines and how to make it and She j ... https: // t.CO/MEXTHNRTIT

— 🌼⁴𝓈𝑜𝓊𝓁 𝓅𝓇𝑜𝓋𝒾𝒹𝑒𝓇₇🌼 Wed Jan 20 19:48:26 +0000 2021

The link has been well documented in a case that links Colombia and Brazil.

In August 2007, an operation that involved police from six countries allowed the capture in Sao Paulo by Juan Carlos Ramírez Abadía, a Colombian drug trafficker who had an extradition request from the United States to export cocaine and for the murder of fifteen people.Ramírez Abadía was a leader of the Cali cartel known for his violent character and eccentric tastes.He had built a complex plot of facade companies and properties in which his two stepsisters participated and, according to his statement, some Spaniards."I was struck that the traffickers had many works of art," Judge Fausto Martin de Sanctis, who saw the cause and established that all the properties of Ramírez Abadía should be considered as the product of his activitycriminal.That included fifteen paintings and engravings by Brazilian artists, with a value of 4 million dollars, which were sent in temporary custody to the Museum of Contemporary Art of the city.

De Sanctis, author a book entitled "Money Landering Through Art" ("Money Laundering through Art"), is a magistrate famous for investigations that have led to prison from characters linked to organized crime to members of the Business Ellite of Brazil.One of those cases involved the Brazilian banker Edemar Cid Ferreira, who came to collect more than one thousand works of art in a suspicious way."He was not a connoisseur, he had no reputation in the art market, but began to buy and buy, at impossible prices," says the judge.In 2006 Ferreira was sentenced to prison for financial and money laundering crimes.The seizure of his works of art required the participation of several security agencies in four countries.

The complexity of money laundering cases through art and other variants motivated Sanctis judge to develop a procedure called “early sale of goods”, which allows to send to auction the properties of a defendant even before the sentence is issued.“If in the end, the defendant is acquitted, the money is returned.If he is convicted, the money passes to a state account, ”explains the magistrate.This procedure allowed to send the properties of the narco Juan Carlos Ramírez Abadía to auction.It also allowed the seizure of more than 200 works of art as part of the investigations for the Lava Jato case, one of the largest corruption scandals of recent times in Latin America.

Luck has been different for others involved in cultural heritage traffic plots linked to corruption in the region.The most obvious case is that of Mateo Goretti, an Italian political scientist to whom the Argentine authorities investigate for alleged money laundering and has also been investigated for aggravated cover -up in a case of theft of cultural goods.In April 2012, Interpol intervened Goretti's domicile at the request of the Prosecutor's Office, which pursued a track.There the agents seized a lot of 58 archaeological pieces whose heritage status should not be unknown to Goretti, an expert in pre -Hispanic art with several published books on the subject.The expertise confirmed that the pieces were part of a stolen collection four years before a museum in the province of Córdoba.The political scientist claims to have fought from the cause, but a review of the case that will be published as part of this investigation demonstrates that this is not true.

Antiquers and museums

One morning of September 2015, the Ambassador of Peru in Buenos Aires presented with a delegation to a warehouse full of boxes with cultural goods seized by the police.In the place it was received by Argentine government officials and specialists from the National Institute of Anthropology and Latin American Thought (INALP), who had been in charge of cataloging a lot with 4.150 pieces.The set included from ceramic vessels and bone musical instruments to a long pre -Columbian cloth of brown and blue stripes that Peruvian diplomats saw surprisingly, as if it were a holy shroud.Actually they were the pieces of a treasure that finished confirming the Lima-Buenos Aires axis as one of the most important routes of cultural goods trafficking in Latin America.In the same enclosure there were pieces that belonged to the cultural heritage of Ecuador.

The objects were the evidence seized to Nestor Janeir, an antiquarian of the Argentine capital that does not appear in the international lists of traffickers, but to whom at the time there were judicial causes in Lima and Buenos Aires for the alleged crime of traffic of cultural heritage traffic.Due to the volume and historical value of the returned pieces - which were packed in more than fifty cardboard boxes - it is the greatest recovery of illicit exported goods in the history of Peru and one of the largest in the continent.

Cultural goods seized by the police in Argentina.

The Janeir case is not the only evidence of the illicit journey that involves the antakers of Buenos Aires.Peru's authorities maintain an investigation initiated in 2012 following the discovery of a stolen bibliographic jewel from the National Library of Lima in a Washington Library that belongs to Harvard University.It was a valuable religious manuscript of the 18th century, written in Quechua, whose loss was not news until a French academic named Isabel Yaya found him while reviewing documents in Dumbarton Oaks, a research center specialized in Byzantine studies and the periodpre-colombino.An institute famous for its collection of rare books, with more than ten thousand volumes.

Yaya communicated the finding to a colleague in Paris, the academic Cesar Itier, an expert in the Quechua language of the colonial era that perfectly knows that type of materials.Itier acknowledged the book: he had studied it in Lima ten years before, and even kept a photocopy in his personal archives.With that image as proof, the academic immediately warned the Washington Library and the Lima authorities.Then it was discovered that Dumbarton Oaks had bought the copy from an antiquarium of the Argentine capital, its supplier of rare materials for almost twenty years.The antiquarian had put the document for sale in its 2011 catalog by 6.500 dollars.

Before an international scandal related to the purchase of stolen cultural goods, Dunbarton Oaks broke out - which asked for a questionnaire to give his version at the beginning of this research, but never answered it - he chose to undo the purchase and claim his money from the antiquarian.The bookseller returned the manuscript to Lima without charge, on condition that his name remained in reserve.In Peru, the return of the manuscript allowed to identify the traffic circuit within the National Library.In Argentina, on the other hand, the case has not been investigated until today.

The traces of the cultural looting of Latin America do not point only from the poor poor to the North Rico.At the beginning of October 2016, international attention returned to the Central American axis due to the seizure of two fragments of the Mayan culture steles that were exhibited in a private museum in the Salvadoran capital and that were reported as stolen in Guatemala from the2013.The pieces come from two Mayan archaeological sites looted in the nineties.The traffickers mutilated them to take them.His whereabouts was unknown until, shortly after launched an international alert, an Interpol officer managed to identify the pieces in the Tesak Foundation Museum, sponsored by Pablo Tesak's family, a missing magnate of the candy industry.

The case was the reason for an intense diplomatic dispute.Guatemala came to send up to eight requests for restitution of the pieces in a period of three years, without positive response, despite the fact that the Central American Convention for the Protection of Cultural Heritage forces the signatory countries to provide technical and legal assistance in cases such as cases such as cases such as cases such asthis.A judge ended more than thirty months of tensions in October, but the dispute did not end.Guatemala claims another 287 archaeological pieces that the Tesak Museum ordered a year earlier from the United States as if it were a repatriation of Salvadoran cultural heritage.They were actually archaeological pieces of Guatemala, and were held by the Customs authorities of El Salvador when they were detected that they lacked clear information about their origin.

"We have unofficial information that the pieces were in Los Angeles, California, when they were imported to El Salvador by the Tesak Foundation," says Eduardo Hernández, head of the Department of Prevention and Control of Illicit Traffic of Cultural Goods of the Ministry of Culture of Guatemala.

In another city of that same state, a stolen piece ended in a church in Mexico: the “Adam and Eve boxes thrown from paradise”, a 18th -century painting that was bought by the San Diego Museum of Art to the antique dealer Rodrigo Rivero Lake,A surround personality character who arouses frequent suspicions in his country and in other parts of Latin America.

In Mexico there is a reserved file of the Attorney General of the Republic that mentions Rivero Lake in a case of theft of a historical piece, although the authorities have declared the details under reserve."There are people involved who have not been arrested to date," says an answer to a transparency request made for the Stolen Memory Project.In Peru, the antiquarian is under suspicion since a repentant trafficker disseminated conversations that apparently negotiate with the antiquarian some pieces stolen from a chapel of the Andes.None of the charges against him have prospered and the antiquarian maintains his lifestyle with frequent appearances in his country's society magazines.

Is good taste a alibi of organized crime?The findings that stolen memory research begins to free from today expose the true beneficiaries of the international scheme that favors the traffic of Latin American cultural heritage: diplomats that abused their dignity, criminals with money for washing, politicians who protect themselves in the gaps ofThe law, alleged art detectives that benefit from tax havens and marches that keep evidence in the back room.The trail of its illegal activities was intangible until the analysis with massive data that we present in this special and that is the beginning of the first census of stolen cultural goods, auctioned or repatriated in the region: more than 50 thousand chips that should enter the record ofThe most unpunished traffickers in the world.

Topics

Did you like this note?Help us maintain this project.

Add

July 5, 2017 at 7:04 pm

A lot is mentioned to art merchants, officials of all kinds and rank, pieces of pieces, destruction of heritage and some people are usually pursued, but what happens with art buyers -which promote the destruction and looting of saidTreasures- When are these banks or large transnational and powerful?They do not touch a single hair of their questioned honor;The cultural authorities at least of Peru, keep silent complicit.The reason?Very simple.These are these companies possessing pre -Columbian cultural heritage collections, viceroynal art, contemporary art, incunable books and everything we can imagine, that they usually solve the existence of museums, finance important archaeological excavations, anthropological research, publications, exhibitions abroadthat organize those same museums and at the same time ensure the salary of directors, archaeologists, workers of these cultural organizations.Double standard?Or am I wrong?

We value the opinion of our community of readers and we are always in favor of the plural debate and the exchange of data and ideas.In this line, it is important for us to generate a space for respect and care, so please keep in mind that we will not publish comments with:- insults, aggressions or hate messages,- misinformation that could be dangerous for others,- information- information- information- informationPersonal- Promotion or Sale of Products.Thank you so much. Cancelar respuesta

Your email address will not be published.The mandatory fields are marked with *

1617